Platoon of soldiers. Preparations for the assault of Winter Palace. October 1917. Aptekarsky island. Petrograd. Russia

Russian Look/Global Look PressThe February Revolution of 1917 brought the 200-year reign of the Romanovs to a close and ended the Russian monarchy forever. The people, tired of autocracy, overthrew Nicholas II. After a few months of political struggle, the left-wing radicals known as the Bolsheviks came to power. Communists would go on to rule Russia for almost 70 years.

As November 2017 nears, marking the 100-year anniversary of the Bolsheviks’ brilliant victory, we have collected all the articles that Russia Beyond has written on this topic. The list, of course, is not final, because there is still much to remember and write about concerning those fateful days.

First things first, the notion of the October Revolution actually taking place in November (and the February Revolution in March) blows people’s minds—and not just foreigners. This was due to a different way of determining dates. Until 1918, Russia used the Julian calendar, which lagged behind the commonly used Gregorian calendar by two weeks.

One of the first things the Bolsheviks did after seizing power was to abolish the use of the Julian calendar. Unlike many of their initiatives, this one brought happiness and comfort to all Russians.

A demonstration of workers from the Putilov plant in Petrograd.

State museum Russia's political history / WikipediaAdmirers of conspiracy theories enjoy speculating about the "hidden reasons" behind the fall of the monarchy. Some believe it was Germans (they were at war with Russia from 1914-1918) or Brits (Russia’s allies) or even Freemasons who plotted the Revolution.

Historians, however, believe that there were logical and rather simple reasons for the anger of the masses. Wearied by World War I, the people longed for peace, but the war continued to drag on and on.

Due to weak infrastructure, civil servants failed to provide the country’s capital, Petrograd (the former name of St. Petersburg) with food. These “bread riots” actually marked the beginning of the uprising.

The peasants, who made up the majority of the Russian population, were dissatisfied with the government. Although Czar Alexander II had freed them in 1861 by abolishing serfdom, by 1917 the majority of these former serfs still had no property to their names. Workers suffered harsh labor conditions that were sometimes outrageous.

Czar Nicolas II and his policies provided reasons for the Revolution as well. By the spring of 1917, even the royalty considered Nicolas II a weak and talentless ruler.

The royal family had been manipulated for years by Grigory Rasputin, a mystic considered a saint, who was hated by the nation. When the Revolution took place most Russians had no loyalty to the monarchy anymore.

The Red Guards, soldiers and sailors, stormed the former Tsar's palace (Winter Palace) in November 1917.

Global Look PressIn 1917, this Marxist party was not the most popular or influential in Russia, and the February Revolution took them by surprise. Their leader, Vladimir Lenin, was in exile in Switzerland along with many other Communists. But they returned to the motherland as soon as possible—and started to act immediately.

People loved the Bolsheviks because they promised to provide peace and property without any need to wait, claiming that the proletariat and peasantry should fight hand-in-hand in their struggle against the bourgeoisie and imperialism.

The Bolsheviks believed in their cause and looked extremely good against the backdrop of indecisive politicians, who were busy mumbling something about a constitutional assembly and democracy during the time between March and October.

Vladimir Lenin, the head of their party, was himself a reason for triumph. A hardworking and fearless revolutionary, he won the hearts of people with his speeches and did all he could to organize the party so that they were able to seize power.

By autumn of 1917, he was more popular than the cunning but weak Alexander Kerensky, who headed the Provisional Government that had been ruling Russia during this period between March and October. Military’s desperate attempt to defeat the Socialists and establish right-wing dictatorship also failed.

Alexander Feodorovich Kerensky (1881-1970) Russian revolutionary leader.

Global Look PressSo, on Nov. 7, 1917, the Bolsheviks led the masses, seized the Winter Palace of Petrograd and overthrew the Provisional Government.

Apart from Lenin, there were a lot of other interesting personalities among the Bolsheviks. For instance, the hardcore revolutionary Leon Trotsky, who was as important to the party as Lenin in 1917. Later, he went on to create the Red Army that helped the Communists to win the Russian Civil War. However, he ended his days in exile after being forced to flee the USSR after losing a power struggle with Stalin.

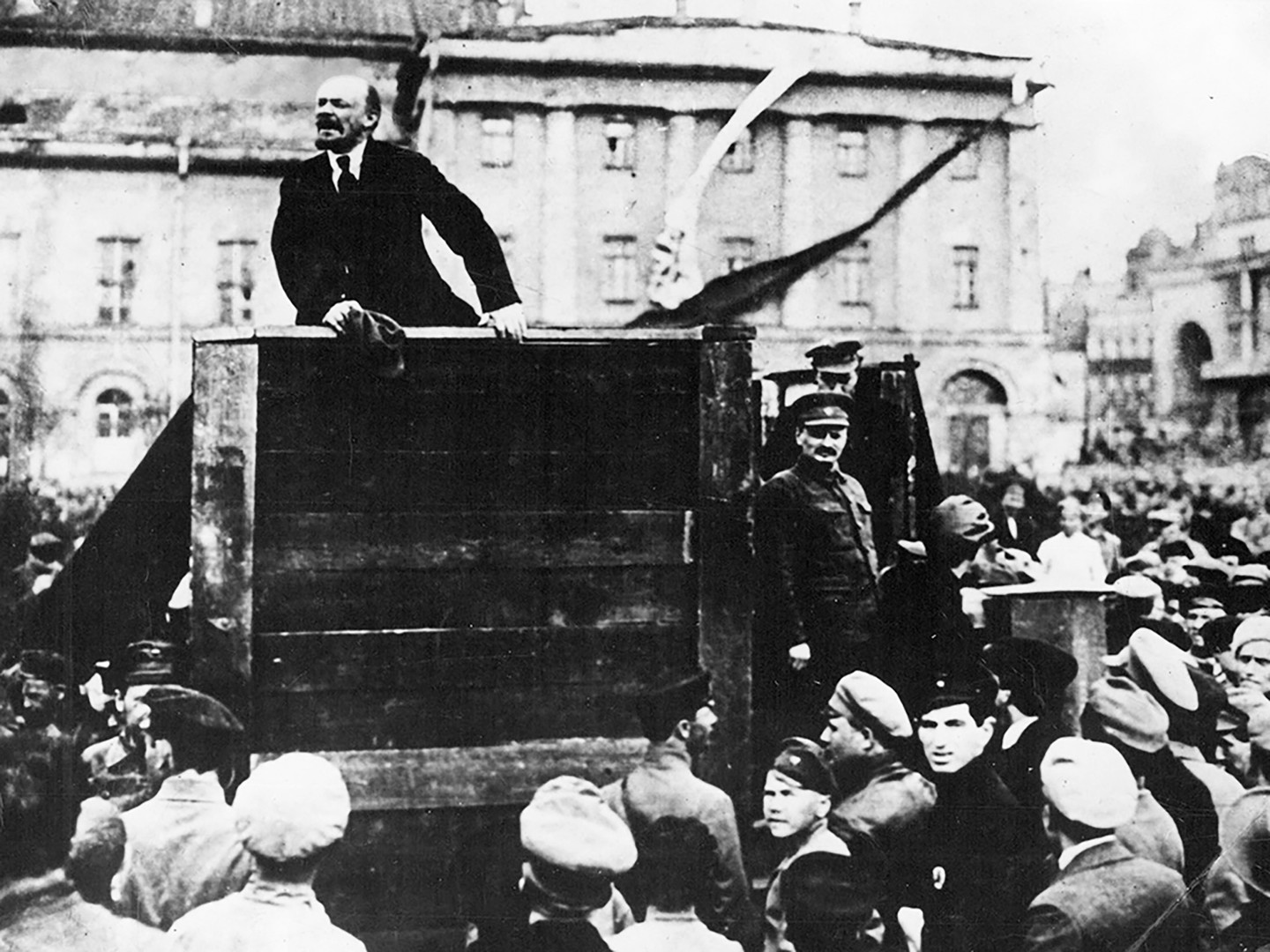

Vladimir Lenin addresses crowd In Petrograd's Sverdlov Square in 1919. Leon Trotsky stands on the right.

Global Look PressNadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s spouse, was also an important revolutionary. She maintained her loyalty to Lenin, and Marxism, through her entire life and helped her husband enormously, despite being jealous of his affair with another revolutionary, Inessa Armand.

The Bolsheviks feared no one because they had a long history of fighting against the state. From the 1890s to the 1900s the party had been illegal in Russia and earned money through violent and unconventional means.

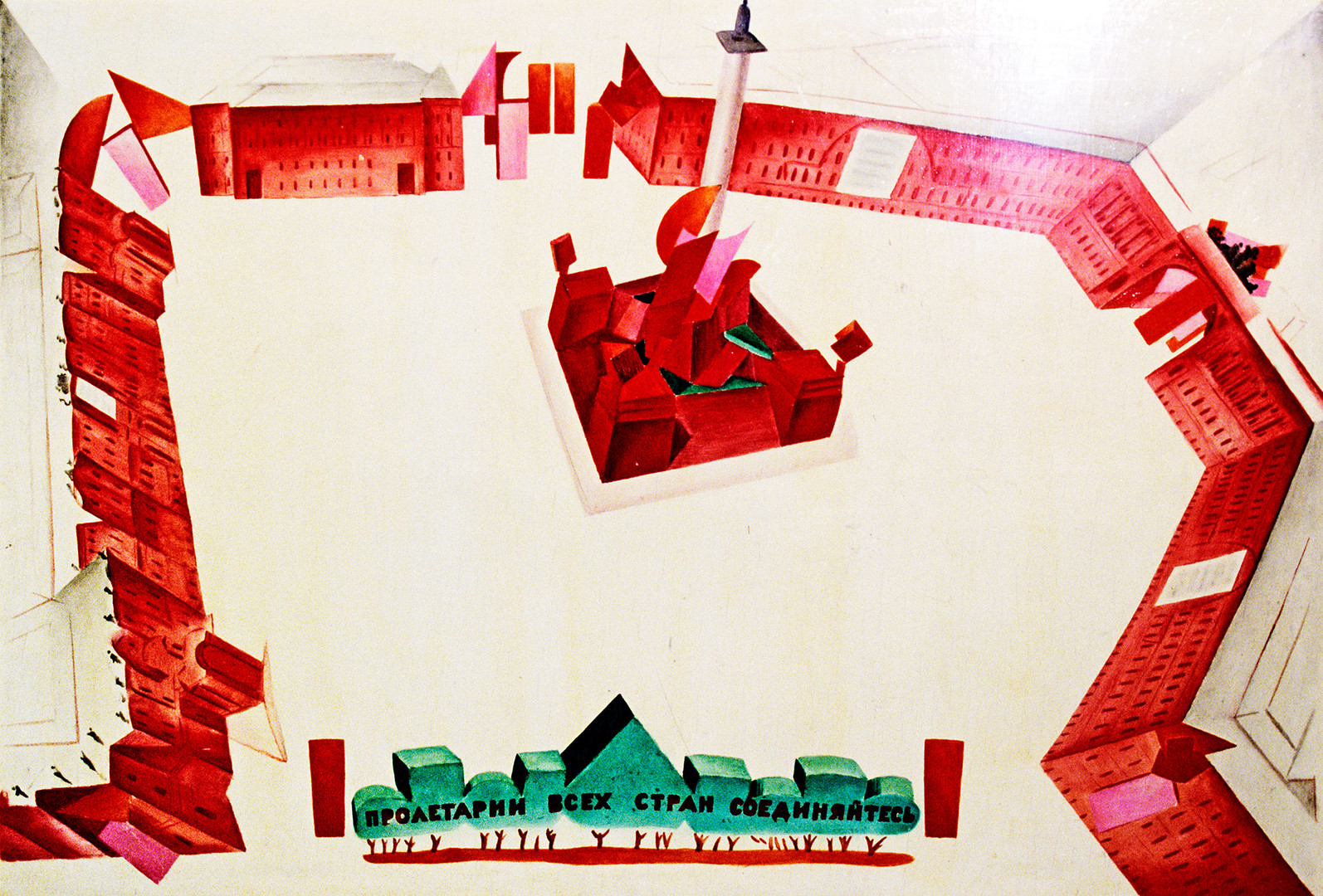

Sketch of decoration for Palace Square by avant-garde painter Nathan Altman (1889-1970).

Rudolf Kucherov/RIA NovostiThe Russian revolutions changed the trajectory of the country forever. Some changes were, of course, for the worse—around 12.5 million people died during the Civil War and people were exhausted by the constant wars and regime changes. For several years, many Russians even became addicted to drugs.

But these events gave Russia a new outlook and new image as well. For instance, avant-garde art is still deeply associated with revolution and socialism as the Russian avant-garde and the Bolsheviks mutually supported each other. The Revolution transformed society and even the way people dressed.

Art reflected the Revolution. People made films and wrote books and poems on this theme— and they still do, actually. Some, like Nobel-prize winner Ivan Bunin, hated the revolution, while others, like poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, could not imagine their lives without it.

In short, foreigners had different reactions. An American journalist John Reed happily supported the Revolution and remained a friend of the USSR to his grave —he is buried in Moscow. On the other hand, the famous British author Somerset Maugham opposed the uprising and, working as a spy, he was sent to Moscow to prevent revolution. Fortunately or not, he failed.

Dozens of foreigners who witnessed the February and October Revolutions (mainly diplomats and journalists) wrote memoirs about that period. “I readily admit that Lenin and Trotsky are both extraordinary men,” wrote George Buchanan, the British ambassador to Russia.

“Everything you want to know…” is an extended guide to the most popular topics about Russia. We constantly work on new material, so this page will be updated with new entries and information as it is received.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox